The Fascination of London

HAMMERSMITH, FULHAM AND PUTNEY

[Pg 1]

HAMMERSMITH

The parish of Hammersmith is mentioned in Doomsday Book under the name of

Hermoderwode, and in ancient deeds of the Exchequer as Hermoderworth. It is

called Hamersmith in the Court Rolls of the beginning of Henry VII.'s reign.

This is evidently more correct than the present spelling of the name, which is

undoubtedly derived from Ham, meaning in Saxon a town or dwelling, and

Hythe or Hyde, a haven or harbour, "therefore," says Faulkner, "Ham-hythe,

a town with a harbour or creek."

Hammersmith is bounded on the south by Fulham and the river, on the west by

Chiswick and Acton, and on the east by Kensington. Until 1834 it was

incorporated with the parish of Fulham, and on Ascension Day of that year the

first ceremony of "beating the bounds" took place. The West London Railway runs

in the bed of an ancient stream which rose north of Wormwood Scrubs and ended at

Chelsea Creek, and this brook was crossed by a bridge at the[Pg

2] place where the railway-bridge now stands on the Hammersmith Road.

The stream was evidently the determining factor in the old parish boundary line

between Kensington and Hammersmith, but Hammersmith borough includes this,

ending at Norland and St. Ann's Roads. On the south side it marches with

Fulham—that is to say, westward along the Hammersmith Road as far as St. Paul's

School, where it dips southward to include the school, and thence to the river.

From here it proceeds midway in the river to a point almost opposite the end of

Chiswick Ait, then northward up British Grove as far as Ravenscourt Gardens;

almost due north to within a few yards of the Stamford Brook Road; it follows

the trend of that road to the North and South Western Junction Railway. It

crosses the railway three times before going northward until it is on a level

with Jeddo Road. It then turns eastward, cuts across the north of Jeddo Road to

Wilton Road West. Northward it runs to the Uxbridge Road, follows this eastward

for a few yards, and strikes again northward up Old Oak Road and Old Oak Common

Road until it reaches Wormwood Scrubs public and military ground. It then trends

north-eastward, curves back to meet the Midland and South-Western Line as it

crosses the canal, and follows Old Oak Common Road until on a level with

Willesden Junction Station, from thence[Pg

3] eastward to the Harrow Road. It follows the Harrow Road until it

meets the western Kensington boundary running between the Roman Catholic and

Protestant cemeteries at Kensal Town. It goes through Brewster Gardens and

Latimer Road until it meets the line first indicated.

HISTORY.

With Fulham, Hammersmith shared in the incursion of the Danes in 879, and it

is especially mentioned in the Chronicle of Roger de Hoveden that they wintered

in the island of Hame, which Faulkner thinks is the ait or island near Chiswick,

which, he says, must have considerably decreased in size during the nine

centuries that have elapsed. In 1647 Cromwell removed his quarters from

Isleworth to Hammersmith, and "when he was at Sir Nicholas Crispe's house, the

headquarters were near the church." The general officers were quartered at

Butterwick, now Bradmore House, then the property of the Earl of Mulgrave.

Perambulation.—The first thing noticeable after

crossing the boundary from Kensington is St. Paul's School. It stands on the

south side of the road, an imposing mass of fiery red brick in an ornamental

style. The present building was erected in 1884 by Alfred Waterhouse, and a[Pg

4] statue to the memory of Dean Colet, the founder, standing within

the grounds was unveiled in 1902. It was designed by W. Hamo Thornycroft, R.A.

The frontage of the building measures 350 feet, and the grounds, including the

site, cover six acres. Dr. John Colet, D.D., Dean of St. Paul's, founded his

school in 1509 in St. Paul's Churchyard, but it is not known how far he

incorporated with it the then existing choir-school. The number of his pupils

was 153, in accordance with the number of fishes in the miraculous draught, and

the foundation scholars are limited to the same number at the present day. The

old school stood on the east side of St. Paul's Churchyard, and suffered so much

in the Great Fire that it had to be completely rebuilt. When, in the nineteenth

century, the site had become very valuable, the school was removed to

Hammersmith, and its original site is now covered by business premises. Dean

Colet endowed the foundation by leaving to it lands that were estimated by Stow

to be worth £120 annually, and that are now valued at over £20,000. The school

is governed under a scheme framed by the Charity Commissioners in 1900, and part

of the income is diverted to maintain the new girls' school in Brook Green.

Lily, the grammarian, was the first headmaster, and the roll of the pupils

includes many great[Pg 5]

names—the antiquaries Leland, Camden, and Strype; John Milton, prince of poets;

Halley, the astronomer; Samuel Pepys; Sir Philip Francis, supposed author of the

"Letters of Junius"; the famous Duke of Marlborough; among Bishops, Cumberland,

Fisher, Ollivant and Lee; among statesmen, Charles, Duke of Manchester, Spencer

Compton (Earl of Wilmington), Prime Minister; and Lord Chancellor Truro; also

Sir Frederick Pollock, Lord Hannen, Sir Frederick Halliday, and Benjamin Jowett.

The preparatory school, called Colet Court, stands opposite on the northern

side of the road. It was founded in 1881, and owns two and a half acres of land.

On the same side Kensington Co-operative Stores covers the site of White

Cottage, for some time the residence of Charles Keene.

Next to the Red Cow public-house lived Dr. Burney, D.D., LL.D., learned

father of a celebrated daughter, who became afterwards Madame D'Arblay. He kept

a school here for seven years from 1786. There are other old houses in the

vicinity, but to none of them is there attached any special interest. The

Convent of the Poor Sisters of Nazareth is in a large brick building on the

south side of the road. This was built in 1857 for the convent purposes. It is

the mother-house of the Nazareth nuns, so that the[Pg

6] numbers continually vary, many passing through for their

noviciate. The nuns collect alms for the aged poor and children, and many of the

poor are thus sustained. Besides this, there are a number of imbecile or

paralytic children who live permanently in the convent. The charity is not

confined to Roman Catholics.

The Latymer Foundation School is a plain brick building standing a little

back from the highroad. It bears the Latymer arms, and a cross in stone over the

doorway, as well as the date of the foundation. The Latymer charity was

established in 1824 by the will of Edward Latymer. He left several pieces of

land in the hands of trustees, who were to apply the rents to the following

uses:

"To elect and choose eight poor boys inhabiting Hammersmith within the

age of twelve and above the age of seven, and provide for every boy a

doublet and a pair of breeches of frieze or leather, one shirt, one pair of

stockings, and a pair of shoes on the 1st of November; and also to provide

yearly, against Ascension Day, a doublet and a pair of breeches of coarse

canvas lined, and deliver the same unto the said boys, and also a shirt, one

pair of stockings, and a pair of shoes; and that on the left sleeve of every

poor boy's doublet a cross of red cloth or baize should be fastened and

worn; and that the feofees should cause the boys to be put to some petty

school to learn to read English till they attain thirteen, and to instruct

them in some part of God's true religion. The allowance of clothing to cease

at thirteen. And that the feofees shall also elect six poor aged men of

honest conversation inhabiting Hammersmith, and provide for every one of

them coats or cassocks of frieze or cloth, and deliver the same upon the 1st

of November in every year, a cross of red[Pg

7] cloth or baize to be fastened on the left sleeve; and that

yearly, on Ascension Day, the feofees should pay to each man ten shillings

in money."

To this charity were added various sums from benefactors from time to time,

and the number of recipients was increased gradually, until in 1855 there were

100 boys and 45 almsmen. At that date the men's clothing consisted of a body

coat, breeches, waistcoat, hat, pair of boots, stockings, and shirt one year,

and the next, great-coat, breeches, pair of boots, stockings, shirt, and hat.

The boys received coat, waistcoat, and trousers, cap, pair of stockings, shirt,

pair of bands, pair of boots. Also on November 1, cap, pair of stockings, shirt,

pair of bands, and pair of boots. At present part of the money is given in alms,

and the rest is devoted to the Lower Latymer School and the Upper Latymer

School, built 1894, situated in King Street West.

At the back of the Latymer Foundation, in Great Church Lane, is the Female

Philanthropic Society. The object is for the reformation of young women

convicted for a first offence or addicted to petty pilfering.

Opposite is a recreation-ground and St. Paul's parochial room, a small

temporary iron building. In King's Mews, Great Church Lane, Cipriani, the

historical painter and engraver, lived at one time. He died here in 1785. The

entrance to[Pg 8]

Bradmore House, the oldest house in Hammersmith, is in the lane. The grounds

stretch out a long way eastward, and one or two old cedars are still growing

here. The eastern portion of the house has a fine front with fluted pilasters,

with Ionic capitals running up to a stone parapet surmounted by urns. The

windows are circular-headed, and those over the central doorway belong to a

great room, 30 feet by 20, and 20 in height. The house, though much altered, is

in its origin part of a very old building named Butterwick House, built by

Edmund, third Baron Sheffield and Earl of Mulgrave, about the latter end of

Queen Elizabeth's reign. The name was taken from a village in Lincolnshire where

the Sheffield family had long lived. This Earl of Mulgrave was grandfather of

John, Duke of Buckingham. He died in 1646, and is buried in the church. The

estate probably passed from the Sheffield family soon after his death, for in

1653 the manor-house or farm of Butterwick, called the Great House, "passed to

Margaret Clapham, wife of Christopher Clapham and widow of Robert Moyle, and her

son Walter Moyle after her." In 1677 it was conveyed by Walter Moyle for the use

of Anne Cleeve and her heirs. She aliened it to Mr. Ferne in 1700. The house was

greatly modernized by Mr. Ferne, Receiver-General of the Customs, who added some

rooms to the north-east, "much[Pg

9] admired," says Lysons, "for their architectural beauty."

He intended this part of the house for Mrs. Oldfield, the actress, but she

never inhabited it. One of Mr. Ferne's daughters married a Mr. Turner, who in

1736 sold the house to Elijah Impey, father of Sir Elijah Impey, Chief Justice

of Bengal. He divided the modern part built by Mr. Ferne from the older

building, and called it Bradmore House, and under this name it was used as a

school for more than a century. It was again divided into two parts, and the

western portion, which fronts the church, is of dark brick with red-brick

facings, which glow through the overhanging creepers.

The older part was sold by the Impey family in 1821, and fifteen years later

was pulled down. Some small houses, which still stand on the south side, with

irregular tiled roofs and walls covered with heavy green ivy, were built on the

site. St. Paul's Church, the foundation-stone of which was laid July, 1882, by

the late Duke of Albany, is opposite. The square pinnacled tower rises to a

considerable height. The original structure was much more ancient. Bowack says:

"The limits of this chapel was divided from Fulham before the year 1622, as

appears in a benefaction to the poor of Fulham."

The chapel of ease to the parish of Fulham was[Pg

10] founded in 1628, and opened in 1631. The whole cost was about

£2,000, of which Sir Nicholas Crispe gave £700. This church was the last

consecrated by Archbishop Laud. The old monumental tablets have been carefully

preserved, and hang on the walls of the present building. The most important

object in the church is a bronze bust of Charles I. on a pedestal 8 or 9 feet

high, of black and white marble. Beneath the bust is the inscription:

"This effigies was erected by special appointment of Sir Nicholas Crispe,

knight and Baronet, as a grateful commemoration of that glorious Martyr Kinge

Charles I. of blessed Memory."

Below, on a pedestal of black marble, is an urn containing the heart of the

loyal subject, and on the pedestal beneath is written:

"Within this Urne is entombed the heart of Sir Nicholas Crispe, knight and

Baronet, a Loyall sharer in yhe sufferings of his Late and Present Majesty. Hee

first setled the Trade of Gould from Guyny, and there built the Castle of

Cormantine. Died 25 Feb. 1665 aged 67 years."

Sir Nicholas Crispe's name is closely identified with Hammersmith. He was

born in 1598, the son of a London merchant, and, though inheriting a

considerable fortune, he was bred up to business. He was subsequently knighted

by King Charles I.,[Pg 11]

and made one of the farmers of the King's Customs. During the whole of the Civil

War he never faltered from his allegiance, but raised money and carried supplies

to the King constantly. He had built Brandenburg House (p.

39), on which he is said to have spent £23,000. This was confiscated by

Cromwell and used by his troops during the rebellion, but at the Restoration Sir

Nicholas was reinstated and rewarded by a baronetcy. His body was not buried at

Hammersmith, but in the church of St. Mildred in Bread Street with his

ancestors. There is a portrait of him given in Lysons' "Environs of London." He

is "said to have been the inventor of the art of making bricks as now practised"

(Lysons). He left £100 for the poor of Hammersmith, to be distributed as his

trustees and executors should think fit. This amount, being expended in land and

buildings, has enormously increased in value, and at the present day brings in a

yearly income of £52 15s. 5d., which is spent on blankets for the poor

inhabitants of the parish. The only other monuments worthy of notice in the

church are those of Edmund, Lord Sheffield, Earl of Mulgrave and Baron of

Butterwick, who died 1646; one of the Impey monuments, which hangs over the

north door, which contains no less than nine names, and another on the wall

close by, to the memory of Sir Elijah Impey and his wife, who are[Pg

12] both buried in the family vault beneath the church. These are

plain white marble slabs surmounted by coats of arms.

There is a monument to W. Tierney Clarke, C.E., F.R.S., who designed the

suspension-bridge at Hammersmith and executed many other great engineering

designs; also a monument to Sophia Charlotte, widow of Lord Robert Fitzgerald,

son of James, Duke of Leinster.

These are all on the north wall, and are very much alike.

On the south aisle hangs a plain, unpretentious little slab of marble to the

memory of Thomas Worlidge, artist and engraver, who died 1766. His London house

was in Great Queen Street, and in it he had been preceded by Kneller and

Reynolds, but in his last years he spent much time at his "country house" at

Hammersmith. Not far off is the name of Arthur Murphy, barrister and dramatic

writer, died 1805. Above the south door is a monument of Sir Edward Nevill,

Justice of the Common Pleas, died 1705. In the baptistery at the west end stands

a beautiful font cut from a block of white veined marble. In the churchyard rows

of the old tombstones, which were displaced when the new church was built, stand

against the walls of the adjacent school. Adjoining the churchyard on the south

there once stood Lucy House, for many generations the home of the[Pg

13] Lucys, descendants of the justice who prosecuted Shakespeare for

deer-stealing.

In the churchyard stand the schools, formerly the Latymer and Charity

Schools, now merely St. Paul's National Schools. The school was originally built

in 1756 at the joint expense of the feofees of Mr. Latymer and trustees of the

Female Charity School, and was restored and added to in 1814. The Charity School

was founded in 1712 by Thomas Gouge, who left £50 for the purpose, which has

since been increased by other benefactions.

On the south side of the church are two picturesque old cottages, which would

seem to be contemporary with the old church itself. Near the north end of the

Fulham Palace Road, which here branches off from Queen Street, is the Roman

Catholic Convent of the Good Shepherd. The walls enclose nine acres of ground,

part of which forms a good-sized garden at the back. The nucleus of the nunnery

was a private house called Beauchamp House. The convent is a refuge for

penitents, of whom some 230 are received. These girls contribute to their own

support by laundry and needle work.

Chancellor Road is so called through having been made through the grounds of

an old house of that name. In St. James Street there is a small mission church,

called St. Mark's, attended[Pg

14] by the clergy of St. Paul's. In Queen Street, which runs from the

church down to the river, there are one or two red-tiled houses, but toward the

river end it is squalid and miserable. Bowack says that in his time (1705) two

rows of buildings ran from the chapel riverwards, and another along the river

westward to Chiswick. One of the first two is undoubtedly Queen Street. The last

is the Lower Mall, in which there are several old houses, including the

Vicarage, but there is no special history attached to any of them. In 1684 a

celebrated engineer, Sir Samuel Morland, came to live in the Lower Mall. Evelyn

records a visit to him as follows:

"25th October, 1695.

"The Abp and myselfe went to Hammersmith, to visite Sir Sam Morland, who

was entirely blind, a very mortifying sight. He showed us his invention of

writing, which was very ingenious; also his wooden Kalendar, which

instructed him all by feeling, and other pretty and useful inventions of

mills, pumps, etc."

Sir Samuel was the inventor of the speaking-trumpet, and also greatly

improved the capstan and other instruments. He owed his baronetcy to King

Charles II., and was one of the gentlemen of the Privy Chamber and Master of

Mechanics. He died in 1696, and was buried at Hammersmith. There are here also

large lead-mills. Behind the Lower Mall is a narrow passage, called Ashen Place;

here is a row of neat brick cottages,[Pg

15] erected in 1868. These were founded in 1865, and are known as

William Smith's Almshouses. Besides the building, an endowment of £8,000 in

Consols was left by the founder. There are ten inmates, who may be of either

sex, and who receive 7s. a week each.

Waterloo Street was formerly Plough and Harrow Lane. Faulkner mentions a

Wesleyan Methodist Chapel here, built in 1809, which probably gave its name to

Chapel Street hard by.

Near the west end of the Lower Mall is the Friends' Meeting House, a small

brick building which, though new, inherits an old tradition; for there is said

to have been a meeting-house here from the beginning of the seventeenth century,

and one of the meetings was disturbed and broken up by Cromwell's soldiers. At

the back is a small burial-ground, in which the earliest stone bears date 1795.

The Lower is divided from the Upper Mall by a muddy creek. This creek can now

be traced inland only so far as King Street, but old maps show it to have risen

at West Acton. An old wooden bridge, erected by Bishop Sherlock in 1751, crosses

it; this is made entirely of oak, and was repaired in 1837 by Bishop Blomfield.

Near the creek the houses are poor and mean, inhabited by river-men, etc., and

the place is called Little Wapping. There is a little passage between creek[Pg

16] and river, and in it is a low door marked "The Seasons." It was

here that Thompson wrote his great poem, in a room overlooking the water, in the

upper part of the Doves public-house, which was then a coffee-tavern. The poem

was so little appreciated by the booksellers, who then combined the functions of

publishers with their own trade, that it was with difficulty he persuaded one of

them to give him three guineas for it.

Opposite is Sussex Lodge, once the residence of the Duke of Sussex, who came

to the riverside for change of air. It was afterwards inhabited by Captain

Marryat, the novelist. Sir Godfrey Kneller lived for a time in the Upper Mall;

and Bowack tells us that "Queen Katherine, when Queen-Dowager, kept her palace

in the summer time" by the river. This was Catherine of Braganza, consort of

Charles II. She came here after his death, and remained until 1692. She took

great interest in gardening, and the elms by the riverside are supposed to have

been of her planting. Her banqueting-hall survived until within the last thirty

years. It was a building with handsome recesses on the front filled by figures

cast in lead. In the reign of Queen Anne the celebrated physician Dr. Radcliffe

lived in the same house. He had the project of founding a hospital, and began to

build, but never carried his intention into effect. He bequeathed the greater

part of[Pg 17]

his property and his library to the University of Oxford, and was the founder of

the famous Radcliffe Library there. Bishop Lloyd of Norwich was a near neighbour

at Hammersmith. He died in the Upper Mall in 1710, and left many valuable books

to St. John's College, Cambridge.

In Kelmscott House, No. 26, lived William Morris, R.A., whose influence on

the artistic development of printing and in many other directions is well known.

On a small outer building of the house is a tablet stating that in this house

Sir Francis Ronald, F.R.S., made the first electric telegraph, eight miles long,

in 1816. Turner, R.A., lived in the Upper Mall, 1808-14, after which he moved to

Sandycombe Lodge, Twickenham. After Riverscourt Road there is a hoarding, behind

which was Queen Catherine of Braganza's mansion already referred to. Mickephor

Alphery, a member of the Russian Imperial Family, took Holy Orders in England in

1618, and lived at Hammersmith. Weltje Street was named after a favourite cook

of George IV.'s, who had a house on its site. He is buried in the churchyard.

Linden House is old, but has no history. Beavor Lodge, which gives its name to

Beavor Lane, was formerly owned by Sir Thomas Beavor. In it now lives Sir W. B.

Richmond, K.C.B., R.A. Old Ship Lane takes its name from a picturesque old

tavern, the Old Ship, the doorway of which[Pg

18] is still standing. Hammersmith Terrace runs from Black Lion Lane

to Chiswick Hall. In it are many old houses remaining. In No. 13 lived P. J. de

Loutherbourgh, an artist and member of the Royal Academy. He died here in 1812.

Arthur Murphy, whose monument in the church has been mentioned, lived at No. 17.

He wrote lives of Fielding, Johnson, and Garrick, besides numerous essays and

plays, and was well known to his own contemporaries. Mrs. Mountain, the

celebrated singer, also had a house in the terrace.

The fisheries of Hammersmith were formerly much celebrated. They were leased

in the seventeenth century to Sir Nicholas Crispe, Sir Abraham Dawes, and others

for the value of three salmon annually. Flounders, smelt, salmon, barbel, eels,

roach, dace, lamprey, were caught in the river, but even in 1839 fish were

growing very scarce. Faulkner, writing at that period, says it was ten years

since a salmon had been caught.

In Black Lion Lane is St. Peter's Church, built in 1829. It is of brick, and

has a high lantern tower and massive portico, supported by pillars. Close by are

the girls' and infant schools, built 1849-52. From this point to the western

boundary of the parish there is nothing further of interest.

In King Street West, after No. 229, there is a Methodist Chapel, with an

ornamental porch. A few doors westward are the new or Upper Latymer[Pg

19] Schools, with the arms of the founder over the doorway. The

buildings are in red brick, with stone facings.

Returning to the north side of the Hammersmith Road, which has for some time

been overlooked, we find the King's Theatre, stone-fronted and new, bearing date

1902. Near it is the West London Hospital, instituted May, 1856, and opened in

July of the same year. Since that time it has been greatly enlarged, and an

immense new wing overlooking Wolverton Gardens has been added. The hospital was

incorporated by royal charter, November 1, 1894. It is entirely supported by

voluntary contributions.

Near the Broadway is the Convent of the Sacred Heart, standing on ground

which has long been consecrated to religious uses, for a nunnery is said to have

existed here before the Reformation. In 1669 a Roman Catholic school for girls

was founded here, and in 1797 the Benedictine nuns, driven out of France, took

refuge in it. The present buildings were erected in 1876 for a seminary, and it

was not until 1893 that the nuns of the Sacred Heart re-established a convent

within the walls. The present community employ themselves in teaching, and

superintend schools of three grades.

There stood in the Broadway until within recent years a charming old building

called The Cottage[Pg 20]—one

of those picturesque but obstructive details in which our ancestors delighted.

Behind the Congregational Chapel there is an old hall, used as a lecture-hall,

which was originally a chapel, and which is said by Faulkner to be the oldest

place of worship in Hammersmith. It was built by the Presbyterians. The first

authentic mention of its minister is in 1700, when the Rev. Samuel Evans

"collected on the brief for Torrington at a meeting of Protestant Dissenters

held at the White Hart, Hammersmith, 13s. 6d."

In the Brook Green Road Nos. 41 to 45 contain an orphanage called St. Mary's

Catholic Orphanage for Girls. On Brook Green itself one or two old cottages with

tiled roofs are still to be seen—reminiscences of old Hammersmith. The long

strip of grass, in shape like a curving tongue, justifies the name of "Green."

Dr. Iles' almshouses, known as the Brook Green Almshouses, have long been

established here, though the present buildings date only from 1839. They stand

at the corner of Rowan Road, and are rather ornately built in brick with

diamond-paned windows. The charity was founded in 1635 by Dr. Iles, who left

"houses, almshouses, and land on Brook Green, and moiety of a house in London."

The old almshouses were pulled down in 1839. At the north end of Brook Green,

next door to the Jolly Gardeners public-house, stood[Pg

21] Eagle House, a very fine old mansion, only demolished within the

last twenty years. Bute House stands on the site. Eagle House was built in the

style of Queen Anne's reign, and had a fine gateway with two stone piers

surmounted by eagles. The back of the house was of wood, and the front of brick,

and there was a massy old oak staircase. Like many other old houses, it became

for a time a school.

Sion House is a square stuccoed building, plain and without decoration either

interior or exterior. This was used as a nunnery until about three years ago,

and the wall decorations in the room used by the nuns as a chapel are still

quite fresh. This room is ugly and meagre, and without attractiveness. It has a

fine garden at the back, stretching out parallel to that of its neighbour, and

the two together embrace an area of close upon four acres, which will make a

fine playground for the projected school. These gardens are at present neglected

tangles of evergreen creepers and trees, but with a little care might be

admirably laid out. On Brook Green is now established St. Paul's School for

girls, a companion to the large school for boys already described. This is

likely to be a very popular institution.

Near the corner of Caithness Road is the Hammersmith and West Kensington

Synagogue, opened on September 7, 1890, which forms one[Pg

22] of the thirteen synagogues in London that constitute together the

United Synagogue, of which Lord Rothschild is the President. The building was

designed by Mr. Delissa Joseph, F.R.I.B.A. The leading features of the design

are a gabled façade with sham minarets, and a recessed porch with overhanging

balcony. The façade is flanked by square towers containing the staircases.

At the south end of the Green there is quite a Roman Catholic colony. The

Almshouses stand on the west side, facing the road, behind a quadrangle of green

grass. They were founded in 1824, and contain accommodation for thirty inmates

of either sex. Five of the houses are endowed, and the pensioners pass on in

rotation from the unendowed to the endowed rooms. They must be Roman Catholics

and exceed the age of sixty years before they are received. On the north side of

the quadrangle is the Roman Catholic parish church, a fine building in the

Gothic style, with a high spire and moulded entrance doorway, built in 1851.

Immediately opposite, across the road, is St. Mary's Training College for

elementary school masters. These young men must have passed the King's

Scholarship examination and be over the age of eighteen before they enter on the

two years' course of study. The large building near on the north side is the

practising-school,[Pg 23]

where the students learn the art of teaching practically. There is a pretty

little chapel in the college, and the walls enclose three acres of land,

including site.

St. Joseph's School for pauper children is adjacent to the practising-school,

on the north side. This building is certified for 180 children, who are received

from the workhouse, etc. They enter at the age of three years, and leave at

sixteen for situations. It was founded and is managed by the Daughters of the

Cross, and was established in its present quarters September 19, 1892. Faulkner

says of Brook Green, "Here is a Roman Catholic Chapel and School called the Arke,"

so that this part of Hammersmith has long been connected with the Catholics.

In the Blythe Road, No. 79, is a fine old house with an imposing portico,

which now overlooks a dingy yard. This is Blythe House, "reported to have been

haunted, and many strange stories were reported of ghosts and apparitions having

been seen here; but it turned out at last that a gang of smugglers had taken up

their residence in it." It was once used as a school, and later on as a

reformatory. It is now in the possession of the Swan Laundry Company.

In Blythe Road there is a small mission church called Christ Church. In

Shepherd's Bush Road, at the corner of Netherwood Road, is West Ken[Pg

24]sington Park Chapel of the Wesleyan Methodists. Shepherd's Bush

and many of the adjoining roads are thickly lined with bushy young plane-trees.

St. Simon's Church, in Minford Gardens, is an ugly red-brick building with

ornamental facings of red brick, and a high steeple of the same materials. It

was built in 1879. St. Matthew's, in Sinclair Road, is very similar, but has a

bell-gable instead of a steeple. The foundation-stone was laid 1870. In Ceylon

Road there is a Board school. Facing Addison Road Station is the well-known

place of entertainment called Olympia, with walls of red brick and stone and a

semicircular glass roof. It contains the largest covered arena in London.

Returning once more to the Broadway, we traverse King Street, which is the

High Street of Hammersmith. It is very narrow, and, further, blocked by costers'

barrows, so that on Saturday nights it is hard work to get through it at all.

The pressure is increased by the electric trams, which run on a single set of

rails to the Broadway. In King Street is the Hammersmith Theatre of Varieties,

the West End Lecture-Hall, and the West End Chapel, held by the Baptists. It

stands on the site of an older chapel, which was first used for services of the

Church of England, and was acquired by the Baptists in 1793. The old tombstones

standing round the present building are memorials of the former burial-[Pg

25]ground. At the west end of King Street is an entrance to

Ravenscourt Park, acquired by the L.C.C. in 1888-90. The grounds cover between

thirty and forty acres, and are well laid out in flower-beds, etc., at the

southern end. The Ravenscourt Park Railway-station is on the east side, and the

arched railway-bridge crosses the southern end of the park. A beautiful avenue

of fine old elms leads to the Public Library, which is at the north end in what

was once the old manor-house.

All this part of Hammersmith was formerly included in the Manor of

Pallenswick or Paddingswick. Faulkner says this manor is situated "at

Pallengswick or Turnham Green, and extends to the western road." The first

record of it is at the end of Edward III.'s reign, when it was granted to Alice

Perrers or Pierce, who was one of the King's favourites. She afterwards married

Lord Windsor, a Baron, and Lieutenant of Ireland. Report has also declared that

King Edward used the manor-house as a hunting-seat, and his arms, richly carved

in wood, stood in a large upper room until a few years before 1813. But the

house itself cannot have been very ancient then, for Lysons says it had only

recently been rebuilt at the date he wrote—namely, 1795. The influence of Alice

Perrers over the King was resented by his courtiers, who procured her banishment[Pg

26] when he died in 1378. After her marriage, however, King Richard

II. granted the manor to her husband.

There is a gap in the records of the manor subsequently until John Payne

died, leaving it to his son William in 1572. This was the "William Payne of

Pallenswick, Esq.," who placed a monument in Fulham Church to the memory of

himself and his wife before his own death, and who left an island called

Makenshawe "to the use of the poor of this parish on the Hammersmith side." This

bequest is otherwise described as being part of an island or twig-ait called

Mattingshawe, situated in the parish of Richmond in the county of Surrey. At the

time the bequest was left the rent-charge on the island amounted to £3 yearly,

which was to be distributed among twelve poor men and women the first year, and

to be used for apprenticing a poor boy the second year, alternately. Sir Richard

Gurney, Lord Mayor of London, bought the manor in 1631. It was several times

sold and resold, and in Faulkner's time belonged to one George Scott. It had

only then recently begun to be known as Ravenscourt. The house was granted to

the commissioners of the public library by the London County Council at a

nominal rent, and the library was opened by Sir John Lubbock, March 19, 1890. In

a case at the head of the stairs are a series of the Kelmscott[Pg

27] Press books, presented by Sir William Morris. Round the walls of

the rooms hang many interesting old prints, illustrative of ancient houses in

Hammersmith and Fulham. There is also a valuable collection of cuttings, prints,

and bills relating to the local history of the parish. In the entrance hall are

hung prints of Rocque's and other maps of Hammersmith, and the original document

signed by the enrolled band of volunteers in 1803. Among the treasures of the

library may be mentioned the minute-book of the volunteers, a copy of Bowack's

"Middlesex," and an original edition of Rocque's maps of London and environs.

Just outside the park, on the east side, is the Church of Holy Innocents,

opposite St. Peter's Schools. It is a high brick building, opened September 25,

1890. There is a Primitive Methodist chapel with school attached in Dalling Road

near by. In Glenthorne Road is the Church of St. John the Evangelist, founded in

1858, and designed by Mr. Butterfield. A magnificent organ was built in it by

one of the parishioners in memory of her late husband.

Behind the church are the Godolphin Schools, founded in the sixteenth century

by the will of W. Godolphin, and rebuilt in 1861. In Southerton Road there is a

small Welsh chapel. The Goldhawk Road is an old Roman road, a fact which was

conclusively proved by the discovery of the[Pg

28] old Roman causeway accidentally dug up by workmen in 1834.

Shepherd's Bush Green is a triangular piece of grass an acre or two in

extent. There seems to be no recognised derivation of the curious name. At

Shepherd's Bush, in 1657, one Miles Syndercomb hired a house for the purpose of

assassinating Oliver Cromwell as he passed along the highroad to the town. The

plot failed, and Syndercomb was hanged, drawn, and quartered in consequence. The

precise spot on which the attempt took place is impossible to identify. It was

somewhere near "the corner of Golders Lane," says Faulkner, but the lane has

long since been obliterated.

St. Stephen's Church, in the Uxbridge Road, was the earliest church in this

part of Hammersmith. It was built and endowed by Bishop Blomfield in 1850. Its

tower and spire, rising to the height of 150 feet, can be seen for some

distance.

St. Thomas's, in the Godolphin Road, is rather a pretty church of brick with

red-tiled roof, and some ornamental stonework on the south face. It was built in

1882, designed by Sir A. Blomfield, and the foundation-stone was laid by the

Baroness Burdett-Coutts. The chancel was added in 1887.

In Leysfield Road stands St. Andrew's Presbyterian Church, of which the

foundation-stone was[Pg 29]

laid by the present Duke of Argyll, March 30, 1870.

In the extreme west of the Goldhawk Road is St. Mary's Church, in bright red

brick, erected 1886. The Duchess of Teck laid the foundation-stone. This has

brought us to the end of the houses. Behind St. Mary's lie waste land and

market-gardens. Just outside the parish boundary are two old houses of brick in

the style of the seventeenth century; they used to be known as Stamford Brook

Manor House, but they have no authentic history. Starch Green Road branches off

from the Goldhawk Road opposite Ravenscourt Park; this road, running up into the

Askew Road, was formerly known by the still more extraordinary name of Gaggle

Goose Green.

In Cobbold Road, to the north of the waste land is St. Saviour's. An iron

church was first erected here in 1884, and the present red-brick building was

consecrated March 4, 1889. The chancel was only added in 1894.

In Becklow Road are a neat row of almshouses with gabled roofs. These are the

Waste Land Almshouses. In the words of the charity report, ordered to be printed

by the Vestry of Hammersmith in 1890, "This foundation owes its origin to a

resolution which was entered into by the copyholders of the Manor on Fulham on

the 23rd April, 1810, that no grants of waste land belong[Pg

30]ing to the manor should in future be applied to the purpose of

raising a fund and endowing almshouses."

Part of the money received from the Waste Lands Fund thus created has been

appropriated to the Fulham side, and part to the Hammersmith side. The

Hammersmith almshouses were at first built at Starch Green. In 1868 these houses

were pulled down and new ones erected. The present almshouses were erected in

1886 for twelve inmates.

In the Uxbridge Road, opposite Becklow Road, is St. Luke's Church, a

red-brick building with no spire or tower, erected in 1872. The iron church

which it succeeded, stands still behind it, and is used for a choir-room and

vestry.

A short way westward, in the Uxbridge Road, is Oaklands Congregational

Church, a somewhat heavy building covered with stucco, with a large portico

supported by Corinthian columns.

Behind the houses bordering the north of the Uxbridge Road is a wide expanse

of waste land with one or two farms. This part of the Manor of Fulham was leased

in 1549 by Bishop Bonner to Edward, Duke of Somerset, under the name of the

Manor of Wormholt Barns. Through the attainder of the Duke the Crown eventually

obtained possession of it. It passed through various hands, and was split up at

last into two[Pg 31]

parts, Wormholt and Eynham lands; these two names are still preserved in

Wormholt and Eynham Farms. In 1812 the Government took a lease of the northern

part of the land for twenty-one years at an annual rent of £100, which was

subsequently renewed. On part of this land was built the prison of Wormwood

Scrubs in 1874. Part is used as a rifle-range, and to the north is a large

public and military ground for exercising troops, etc. To the east of the prison

are the Chandos and the North Kensington cricket and football ground.

The Prison walls enclose an area of sixteen acres. The building was all done

by convict labour. To the south, without the walls, lie the houses of the

officials, warders, etc. On the great towers by the gateway are medallions of

John Howard and Elizabeth Fry. Within the courtyard are workshops, etc., and

immediately opposite the gateway is a fine chapel with circular windows built of

Portland stone. Four great "halls" stretch out northward, at right angles to the

gates. These measure 387 feet in length, are four stories in height, and each

provides accommodation for 360 prisoners. The three western ones are for men,

that on the east for women. On the male side one "hall" is reserved for convicts

doing their months of solitary confinement before passing on elsewhere. The men

are employed as masons, carpenters, etc., the women in laundry and needle-work.

The exercise-[Pg 32]grounds

are large and airy; the situation is very healthy.

The next district, traversed by the Latymer Road, is a squalid, miserable

quarter of the borough, with poor houses on either side. In Clifton Street is

St. Gabriel's, the mission church of St. James's, a little brick building

erected in 1883 by the parishioners and others.

Further northward, beyond the railway-bridge, is Holy Trinity Church. The

foundation-stone was laid on Ascension Day, 1887, by the Duchess of Albany. It

is a red-brick building with a fine east window decorated with stone tracery.

Beyond this there is nothing further of interest except St. Mary's Roman

Catholic cemetery at Kensal Green. It comprises thirty acres, and was opened in

May, 1858. There are many notable names among those buried here, namely:

Cardinals Wiseman and Manning; Clarkson Stanfield, R.A.; Dr. Rock, who was

Curator of Ecclesiastical Antiquities in the South Kensington Museum; Adelaide

A. Proctor, Panizzi, Prince Lucien Bonaparte, and others. To the west of the

cemetery lies a network of interlacing railways, to the north a few streets, in

one of which there is an iron church.

We have now made practical acquaintance with this vast borough, stretching

from the river to Kensal Green, and including within its limits an[Pg

33] exceptional number of churches and chapels of all denominations.

There are numerous convents, almshouses, and schools. Hammersmith has always

been noted for its charities, and no bequest to its poor has ever been made

without being doubled and trebled by subsequent gratuities. On a general survey,

the three most interesting places within the boundaries seem to be: St. Paul's

School, flourishing in Hammersmith, but not indigenous; Ravenscourt Park, with

its aroma of old history, and the sternly practical institution of Wormwood

Scrubs Prison. Hammersmith can boast not a few great names among its residents,

by no means least that of the loyal Sir Nicholas Crispe; but with Kneller,

Radcliffe, Worlidge, Morland, Thompson, Turner, and Morris, it has a goodly

list.

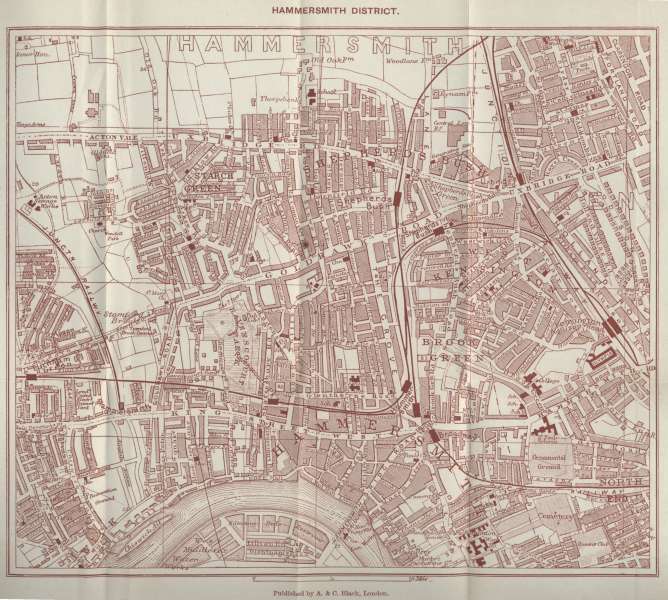

HAMMERSMITH DISTRICT.

HAMMERSMITH DISTRICT.

Published by A. & C. Black, London.