GREAT BRITAIN

Shortly after the War began,

an "Exhibition of German and Austrian Articles typifying Design" was

arranged at the Goldsmiths’ Hall, to show the directions in which we had

lessons to learn from German trade-competitors as to the combination of

Art and economy applied to ordinary articles of commerce. The walls were

hung with German posters, and one felt at once that while our average

poster cost perhaps six times as much to produce, it was inferior to its

German rival in just those vital qualities of concentrated design,

whether of colour or form, and those powers of seizing attention, which

are essential to the very nature of a poster.

While we have had individual poster artists, such as Nicholson, Pryde,

and Beardsley, whose work has touched perhaps a higher level than has

ever been reached on the Continent, our general conception of what is

good and valuable in a poster has been almost entirely wrong. The

advertising agent and the business firm rarely get away from the popular

idea that a poster must be a picture, and that the purpose of every

picture is to "point a moral and adorn a tale." They seldom realise that

poster

art and pictorial art have essentially different aims. If a British firm

wishes to advertise beer, it insists on an artist producing a picture of

a publican’s brawny and veined arm holding out a pot of beer during

closed hours to a policeman; or a Gargantuan bottle towering above the

houses and dense crowds of a market-place; or a fox-terrier climbing on

to a table and wondering what it is "master likes so much"—all in

posters produced at great expense with an enormous range of colour. The

German, on the other hand—there was an example at the Goldsmiths’

Hall—designs a single pot of amber, foaming beer, with the name of the

firm in one good spot of lettering below. It is printed at small cost,

in two or three flat colours; but it shouts "beer" at the passer-by. It

would make even Mr. Pussyfoot thirsty to glance at it.

Our British love for a story in a picture has accounted for an

immense amount of ingenious artistry falling into amorphous

ineffectiveness. It is the essence of the poster that it should compel

attention; grip by an instantaneous appeal; hit out, as it were, with a

straight left. It must convey an idea rather than a story. From its very

nature it must be simple, not complex, in its methods. If it has

something eccentric or bizarre about it, so long as it is good in

design, that is a good quality rather than a fault. Even about the best

of our war posters one feels that they are too often enlarged drawings,

excellent as lithographs to preserve in a collector’s portfolio, but

ineffective when valued in relation to the essential services that a poster is required to

render. We must regretfully admit that when it comes to choosing

illustrations for a volume such as this on their merits as posters, not

as pictures, it is difficult not to give a totally disproportionate

space to posters made in Germany.

Our British war posters are too well known and too recent in our

memory to require any lengthy introduction or comment. The first

official recognition of their value to the nation was during the

recruiting campaign which began towards the close of 1914. The

Parliamentary Recruiting Committee gave commissions for more than a

hundred posters, of which two and a half million copies were distributed

throughout the British Isles. We hope it is not true that, in their

wisdom and aloofness, they refused the offer of a free gift of a

six-sheet poster by Mr. Frank Brangwyn, R.A. It is, at

any rate, certain that they possessed a poor degree of artistic perception,

and, added to this, a very low notion of the mentality of the British

public. Hardly one of the early posters had the slightest claim to

recognition as a product of fine art; most of them were examples of what any

art school would teach should be avoided in crude design and atrocious

lettering. Among the best and most efficient, however, may be mentioned

Alfred Leete’s "Kitchener." But if one compares Leete’s head of Kitchener,

"Your Country Needs You," with Louis Oppenheim’s "Hindenburg," the latter,

with its rugged force and reserve of colour, stands as an example of the direction in which Germany tends to beat us in poster art.

While these early official posters perhaps served their purpose—and if

they did, it was thanks to the good spirit of the British public and not to

the artistic merit of the posters themselves—a series of recruiting posters

was issued by the London Electric Railways Company. Even before the War,

this Company, or rather their business manager, Mr. F. Pick (for in regard

to posters Mr. Pick might well say "L’état, c’est moi"), was setting an

example in poster work by securing the services of the best artists of the

day. Their recruiting posters were a real contribution to modern art. They

served their purpose, and at the same time were dignified in conception,

design, and draughtsmanship. Standing high among them in nobility of appeal

and power of drawing were Brangwyn’s "Britain’s Call to Arms," and Spencer Pryse’s

"Only Road for an Englishman."

Though they were not issued till 1916, we might mention here the

series published by the London Electric Railways Company at the time

when the restrictions regarding paper prevented the general distribution

of posters at home. It was then that the Company thought of the friendly

idea of sending to our troops overseas a greeting of the kind so many of

them had been familiar with in old days in London. Four posters, to

awaken thoughts of pleasant homely things, were sent out for use in

dug-outs and huts in France and other places abroad. Each was headed with the words:

"The Underground Railways of

London, knowing how many of their passengers are now engaged on important

business in France and other parts of the world, send out this reminder of

home." The drawings were the free gifts of the artists who designed

them—George Clausen, R.A., Charles Sims, R.A., F. Ernest Jackson, and J.

Walter West. It was a most admirable idea, admirably carried out, and, as

were their recruiting posters, a pronounced testimony to the patriotic and

disinterested attitude of a great business institution. Everyone who served

abroad knows how much these posters were appreciated as a decoration in Army

messes, Y.M.C.A. huts, and elsewhere.

To return to the official use of posters, very much better work was

produced in 1915 by the Parliamentary Recruiting Committee, and also under

the auspices of the Ministry of Information, the authorities having learned

at last that, at home, a poster might be a work of art, and that, abroad, an

"official artist" might be deemed worthy of a subaltern’s rank, rations, and

emoluments. Among good posters for which the Government was at this time

responsible may be mentioned Bernard Partridge’s "Take up the Sword of

Justice," Guy Lipscombe’s "Our Flag," Doris Hatt’s "St. George," Caffyn’s "Come along, Boys," and Ravenhill’s

"The Watchers of the Seas." In this

connection it is amusing to recall a wireless message circulated from Berlin

on October 2, 1915, in which appeared the statement: "To-day the

exhibition of all English recruiting posters published up to the present was

opened for the benefit of the German Aeronautic Fund. The exhibition is a

great material success, notwithstanding the general disappointment at the

poor and inartistic designs." It is, of course, an essential part of

national propaganda to decry the quality of whatever is produced by the

enemy; but we must admit that in this instance some truth was embodied in

the judgment of these hostile critics. It came as a wholesome counterblast

to the probably inspired laudatory articles which a little before this date

had appeared in our own Press telling us of "several million of forceful and

often fine" posters, and that "the hoardings of England have never borne a

better message conveyed in a better manner." That many of the posters were

comparative failures goes without saying: and there was one real blunder. In

connection with the War Savings Campaign the Ministry had the excellent idea

of using as a poster Whistler’s famous masterpiece—his "Portrait of the

Artist’s Mother," now in the Louvre. Nothing could have been better: but

then they got someone to write across the beautiful background, in paltry

lettering, "Old age must come." There could be no better example of our

British idea of enforcing a moral. It was an act of vandalism—impossible in

France—almost as cruel as the firing of a shell into Rheims Cathedral. And

Whistler, who spent hours in considering where he should place his dainty

little butterfly signature, must have turned in his grave, or wished that he could have returned to earth to produce a new

edition of his "Gentle Art of Making Enemies."

To Mr. G. Spencer Pryse belongs the honour of first realising in

actual productions the needs of the time. Mr. Pryse was in Antwerp at

the outbreak of war, and thus was an eye-witness of much of the tragedy

which overtook Belgium. On the actual scenes of the evacuation were

founded his pathetic lithograph of the Belgian refugees struggling into

steamers to escape from the advancing terror. Shortly after, he obtained

a commission to act as a despatch-rider for the Belgian Government, in

which capacity he visited all parts of the front line both in Belgium

and in France, and saw a good deal of desultory fighting. Before he was

wounded, he drew several of the series of nine lithographs entitled "The

Autumn Campaign, 1914," which were published early in 1915. His poster "The Only Road for an Englishman" was of the same period, followed soon

afterwards by his powerful pictorial appeal on behalf of the Belgian Red

Cross Fund. It is interesting to know that even under the most difficult

conditions, and under fire, his drawings were made, not on paper, but on

actual lithographic stones carried for the purpose in his motor-car.

The outstanding figure among poster artists, both in quantity and for

technical accomplishment, was Mr. Frank Brangwyn, R.A. His "Britain’s

Call to Arms" was produced in 1914 by the Underground Railways Company,

and circulated in large numbers. The huge lithographic stone upon which this was drawn was

subsequently presented, as the joint gift of Sir Charles Cheers

Wakefield, Lord Mayor of London, and the artist, to the Victoria and

Albert Museum, where it is preserved and exhibited. His invention and

activity as a designer of war posters were very considerable. The number

of poster designs from his hand produced during the War is at least

fifty, without taking into account such additional work as the

propaganda lithographs published by the Ministry of Information. Though

Mr. Brangwyn’s first war poster was prepared in conjunction with the

Underground Railways, he was always willing and eager to make designs

for any deserving cause, and among the committees he assisted by his

vigorous work may be named the 1914 War Society, the Belgian and Allies’

Aid League, the National Institute for the Blind, and the Daily Mail

Red Cross Fund. Practically all these posters were done as a free gift

by the artist; and their number and quality stand as a splendid record

of national service. Heaven preserve Mr. Brangwyn from an O.B.E.! But

one wonders whether the Government has no suitable reward for one who

spared no effort and sacrificed himself and his time and talent in a

purely impersonal desire to serve his country.

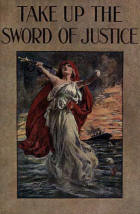

BERNARD PARTRIDGE.

"Take Up the Sword of Justice."

Parliamentary Recruiting Committee:

Poster

No. 106.

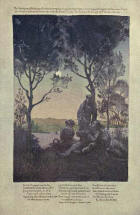

F. ERNEST JACKSON.

"Song to the Evening Star."

One four posters sent out by the Underground Electric

Railways Company of London for use in dug-outs, etc., Christmas, 1916.

FRANK BRANGWYN, R. A.

"Britain’s Call to Arms."

Recruiting poster, published by the Underground Electric

Railways Company of London, 1914. The stone upon which Mr. Brangwyn drew

this lithograph—the first great poster of the War—was subsequently presented

to the Victoria and Albert Museum.

J. WALTER WEST.

"Harvest-Time, 1916: Women’s Work on

the Land."

Issued by the Underground Electric Railways Company of

London.

GERALD SPENCER PRYSE.

"The Only Road for an Englishman.

Through Darkness to Light;

Through Fighting to Triumph."

Published by the Underground Railways Company of London,

Ltd., 1914.

GEORGE CLAUSEN, R.A.

"Mine Be a Cot Beside the Hill."

One of four posters sent out by the Underground Electric

Railways Company of London, for use in dug-outs, huts, etc.,

Christmas, 1916.

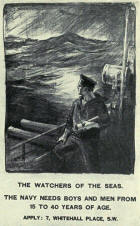

L. RAVEN-HILL.

"The Watchers of the Seas."

Recruiting poster for the British Navy, 1915.

BERNARD PARTRIDGE.

"Kossovo Day Is the Serbian National

Day."

Poster of a British "Flag Day." 25th June, 1916.

BERNARD PARTRIDGE.

"Haven."

Poster of the British Women’s Hospital Fund, appealing for

subscriptions toward the "Star and Garter" home for men disabled by the War.

FRANK BRANGWYN, R.A.

"At Neuve Chapelle."

British Recruiting Poster.